It’s a fairly rare thing that medieval literature makes the news. But this morning, I woke up see that a slew of papers from the New York Times to the dear old Daily Mail were excitedly proclaiming the solution of a ‘Chaucer mystery’. The discovery is published in the current issue of The Review of English Studies, and nicely summed up here.

The gist of it is that, by carefully re-reading a fragmentary medieval manuscript, scholars Seb Falk and James Wade hit on a new interpretation of Chaucer’s references to an obscure ‘Wade,’ whose tale he seems to have expected his readers to know. In previous transcriptions of the fragmentary text, scholars thought the story in question was about ‘elves and adders’ and ‘sprites that dwell by the water’: Falk and Wade argue that a more correct reading would be ‘wolves and adders’ and ‘sea snakes that dwell by water’. This, they contend, is important: the story Chaucer is referring to isn’t some fey fairytale about otherworldly beings, but a fine rousing chivalric romance.

It got me thinking about which kinds of correction are seen as important, and why - and especially, how our ideas about gender and about ‘highbrow’ and ‘lowbrow’ types of art or craft, play into that.

As I was pondering this, I came across another bit of medieval news, this time about the return of the Bayeux Tapestry to England. In his piece, historian David Musgrove swiftly wards off any potential nit-pickery with an acerbic aside just two sentences down. ‘If anyone is worried about me flipping indiscriminately between tapestry and embroidery, rest assured that I am fully aware that the Bayeux Tapestry is in fact an embroidery. … Everyone knows it as the Bayeux Tapestry though, and I’m not about to start advocating for the Canterbury Embroidery because that just doesn’t have the vibe.’ I love a good apotropaic footnote as much as anyone, and I can admire the chutzpah of a footnote that is one step up from Nikolai Berdyaev’s famous defence ‘this came to me in a dream’.

But I think it matters, this kind of textile ‘detail’. And I think it matters for reasons that can also tell us something about Chaucer, and how his reputation is re-made in and out of the public eye.

In the Legend of Good Women, Chaucer retells the Classical myth of Philomela. It was a well known story. The Thracian king Tereus marries the Athenian princess Procne, but falls into a mad lust for her sister Philomela. He rapes her, then imprisons her in the wilderness, cutting out her tongue so she cannot say what he has done. However, she weaves the story of the rape into a textile, and has it sent to her sister Procne. The two women engineer a horrific revenge on Tereus - killing his children and serving their cooked flesh to the unsuspecting father - and, at last, the gods intervene and transform all three characters into birds.

In most medieval and Classical versions of the story of Philomela, the textile the raped woman creates is a thing of enormous beauty and value. Its aesthetic qualities are described with lingering poetry. Modern scholars have seized eagerly on the idea that the ‘voice of the shuttle’ (Aeschylus’ phrase, out of the Greek - it’s all we have of a lost tragedy of his retelling this story, and isn’t it haunting?) could represent Philomela’s own lost feminine language. If that’s true, then the beauty of what Philomela weaves is very important: either it’s as a powerful demonstration that women’s eloquence cannot be silenced by male violence, or - rather less cheerfully - it’s evidence that, even while women try to communicate about rape, men will exploit what they create and turn it into something decorative or saleable.

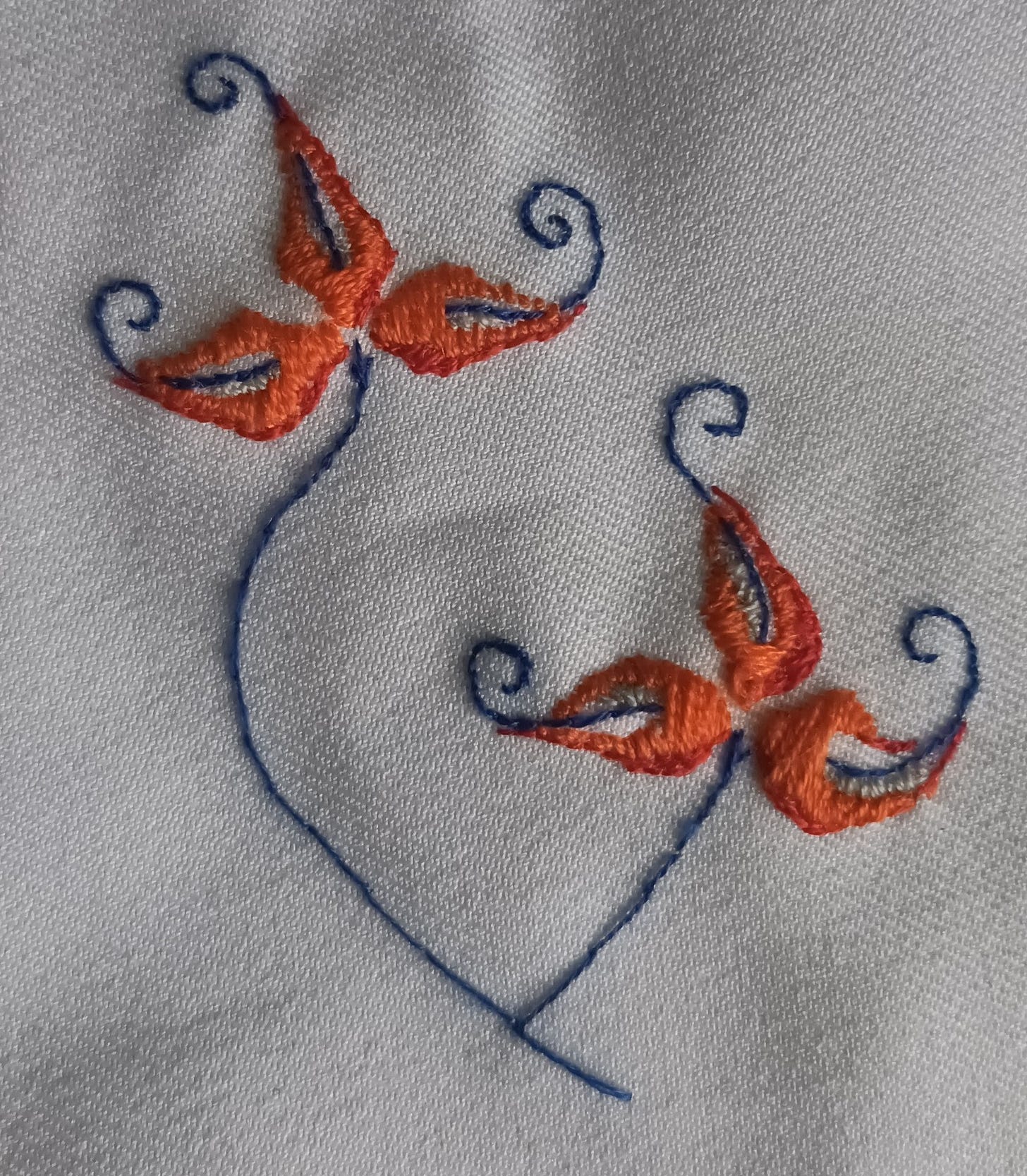

Chaucer - rather unexpectedly, given his track record - does something quite different. He does describe Philomela’s skill with textile work. Early in his narrative, we hear that, as a young girl, Philomela learned to ‘work and embroider’; she also learned ‘to weave her cloth on her stol’. A ‘stol’ is frame, such as one would use while making embroidery or small-scale weaving. The Middle English Dictionary refers to ‘stol-work’ on orpheys - the decorative bands on priests’ vestments or knights’ robes - as an illustration of the term. So, what we’re imagining here is fine, small-scale weaving and embroidery, of the kind that uses expensive materials.

But when Chaucer comes to describe Philomela’s textile work after the rape and the violence that robs her of her tongue, he tells a different story. There is no hint that what Philomela weaves is beautiful at all. He tells us her woven tapestry is ‘large’ - and it must be; it takes her a year - but the word he uses to describe it is stamin. In Middle English, ‘stamin’ is cloth made from wool; it is the kind of cloth used for upholstery, or worn by hermits and nuns as a substitute for a hair shirt. Nothing about it suggests beauty or luxury at all.

There’s a long history of scholars dismissing the particularity of textile work. It’s women’s work; it’s domestic work. It’s craft and not art; it’s decorative, not creative. And perhaps it’s for this reason that most scholars, reading Chaucer, mash together his two very different descriptions of Philomela’s textile work, the earlier fine embroidery and the later coarse woven tapestry. They miss the point that Chaucer is making: that Philomela is not producing beauty from pain; her rape does not result in a textile whose aesthetic value can be exploited. What she makes is rough and uncomfortable: it is a textile that refuses to embroider over the ugliness of male sexual violence.

Why does it matter? Well, I think it matters that we do not relegate textile work - craft work, women’s work - to the footnotes, because when we do that, we lose the ability to understand that work and its meaning. We misread Chaucer, and more than that, we misread the rape. And while we are thinking about how to re-read Chaucer more accurately, I think it also matters that we read his textile fictions as carefully as we read his chivalric references to more masculine narratives.

***

I make this argument at more length in my book, Female Desire in Chaucer’s Legend of Good Women and Middle English Romance (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2020). NB: in that book, I suggest stol-work embroidery was carried out on woven silk; I would now say it was worked on woven linen, with silk.

Fabulous insight on the contrast between "stol-work" and "stamin" that's easy to overlook in those few lines. Thanks for sharing. --Candace

Thank you for writing this, it was fantastic!